Match Points

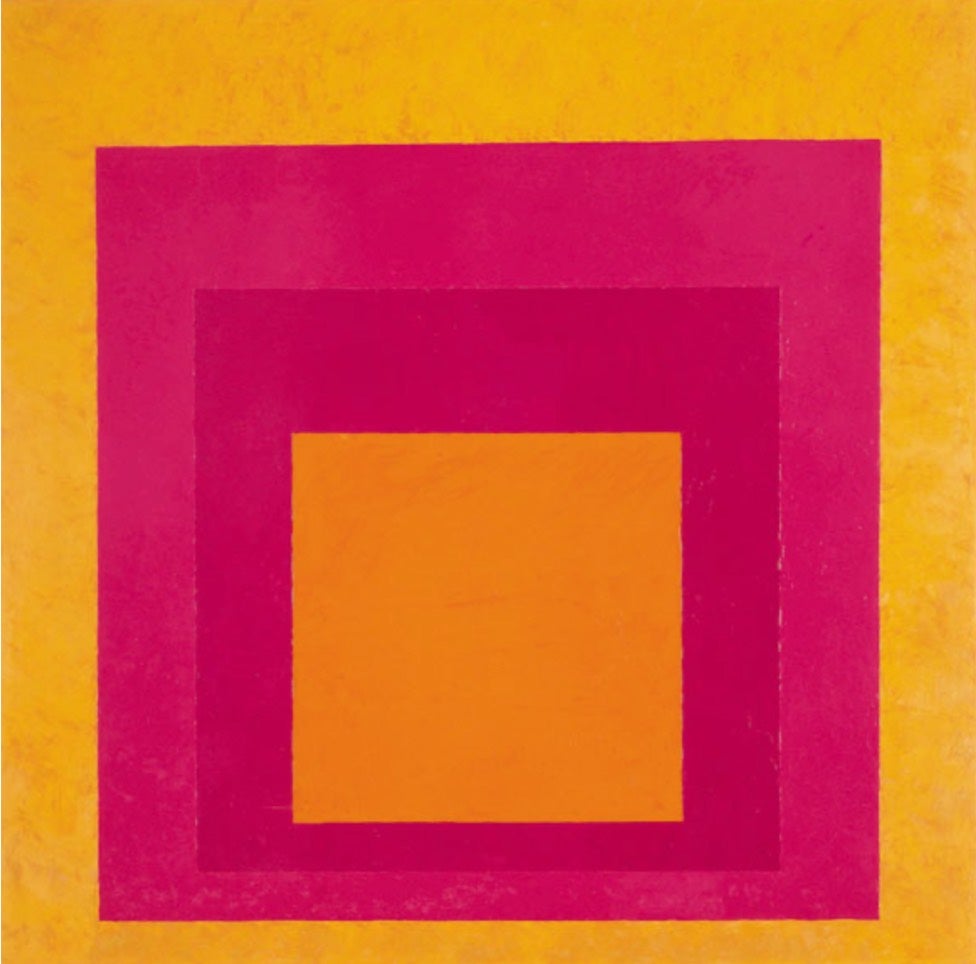

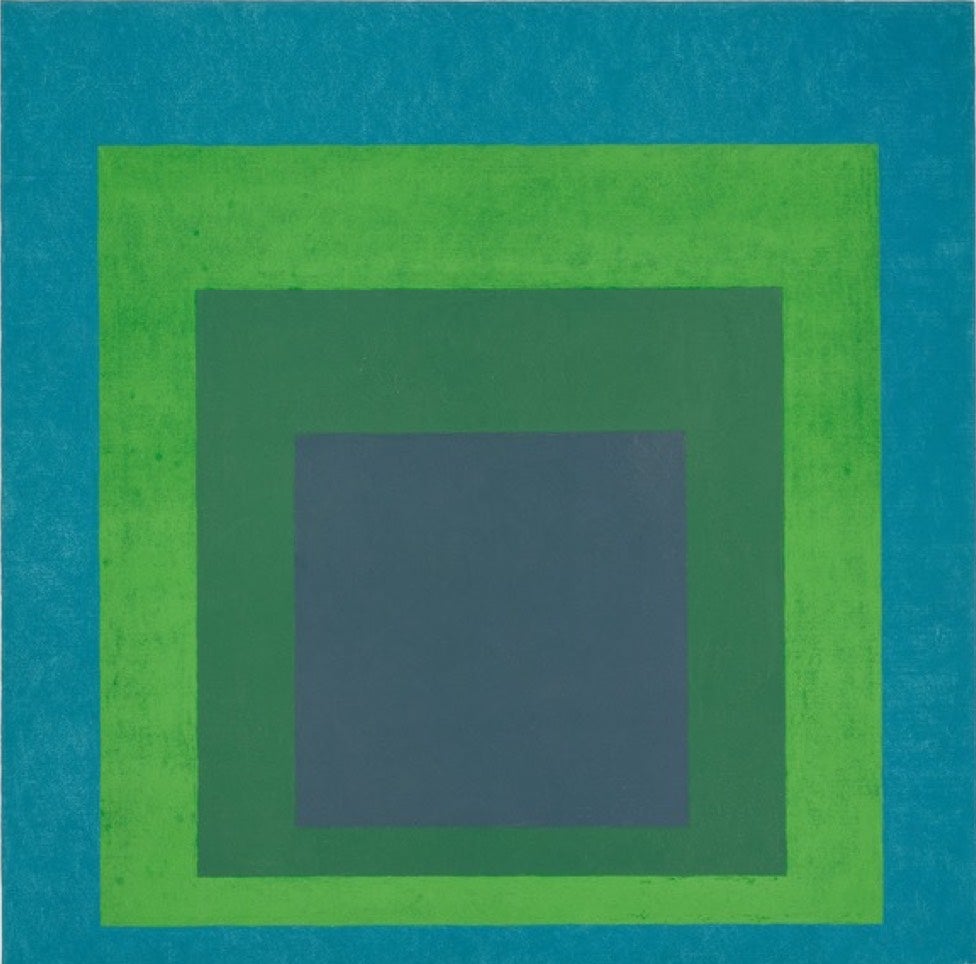

The painter Josef Albers took the humble square and turned it into a study in how certain combinations of color can create magical effects on mood and seeing. He taught Johns and Rauschenberg, and he made Judd think twice. Look closely, and his work will reveal the secrets why certain colors look good togetherIn 1950, Josef Albers painted Homage to the Square for the first time: a yellow square inside an orange square inside a sky-blue square inside a blue-grey square. He was 62. Over the next 26 years, he would paint variations of this arrangement more than a thousand times. He finished his last one just weeks before his death at 88.

It’s tempting to slot Albers into that most hopeful species of artist, the late bloomer, along with Cervantes, who published Part One of Don Quixote at 58 and Part Two 10 years later. Like Cervantes, who started writing in prison, Albers produced his first Homage seemingly oblivious to the turbulence of his life—he’d just quit his teaching position at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and moved to New York City, not the easiest place to achieve serenity for a senior citizen with no immediate prospects.

But from the first Homage, Albers proceeded with absolute assurance: From then on, the format never varied, two or three or four nested squares of solid colors straight from the tube, with all of the squares resting below the center of the frame, so their bottom edges seem to settle to the earth and their widening upper edges seem to reach for the sky. A set of stacking wood tables he built in his early days teaching at the Bauhaus—before he and his wife, Anni, who was Jewish, left Berlin for North Carolina, in 1933—have a similar airy structure and craftsmanlike satisfaction.

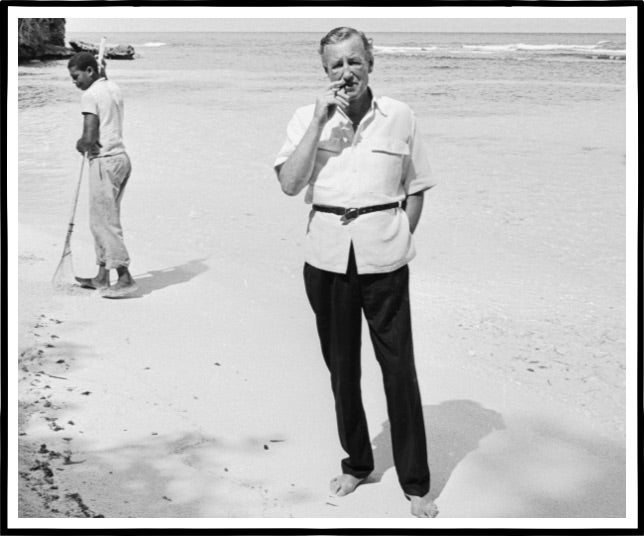

From top: Albers, photographed at the age of 77, and a painting dated 1964; a sketch made by Albers when he was a member of the Bauhaus.

From top: Albers, photographed at the age of 77, and a painting dated 1964; a sketch made by Albers when he was a member of the Bauhaus.

Inside this immediately recognizable configuration, he fit a lifetime of experimentation in color. Months after his first Homage, Yale hired him to run their newly formed graphic design department; for his students the Homage series served as object lessons of how much pure color could do. Through trial and error, he found combinations of colors that could create illusions when set beside each other, disappearing like tissue or leaping out in one arrangement, shimmering in another. The same colors in reverse order could cast completely different moods, as in his pair of yellow, orange, and gold Homage paintings that he subtitled Tenacious (1969) and Warm Silence (1971).

He taught a tremendous number of influential artists how “to open eyes”—the pet phrase of a non-native speaker who once called “pasture” the opposite of “future.” The roll call of former Albers students sounds like a short list of the canon of mid-century contemporary art: Ruth Asawa, Cy Twombly, Richard Serra, and Robert Rauschenberg, who said, “I consider Albers the most important teacher I’ve ever had, and I’m sure he considered me one of his poorest students.”

ANYTHING BUT SQUARE

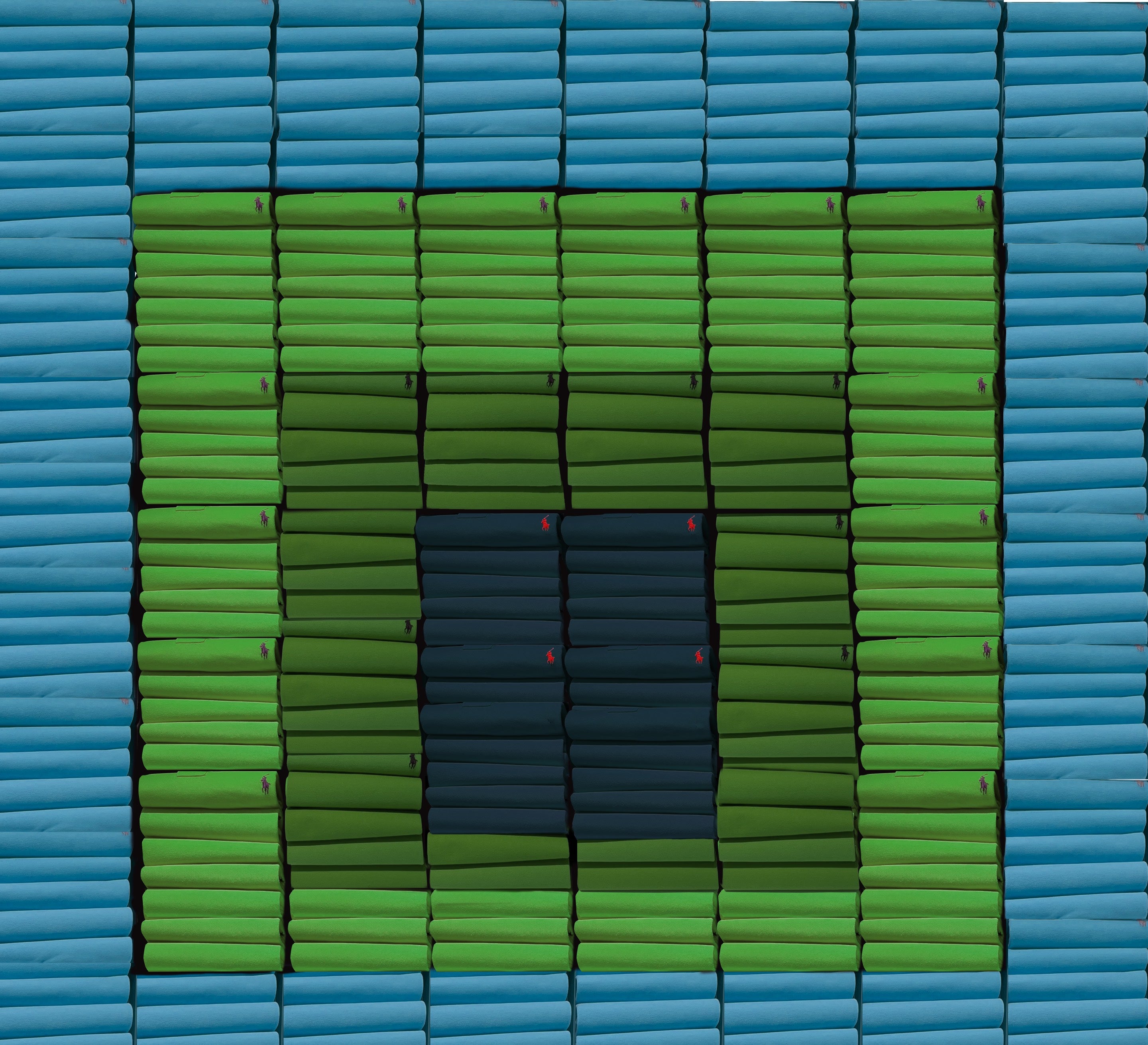

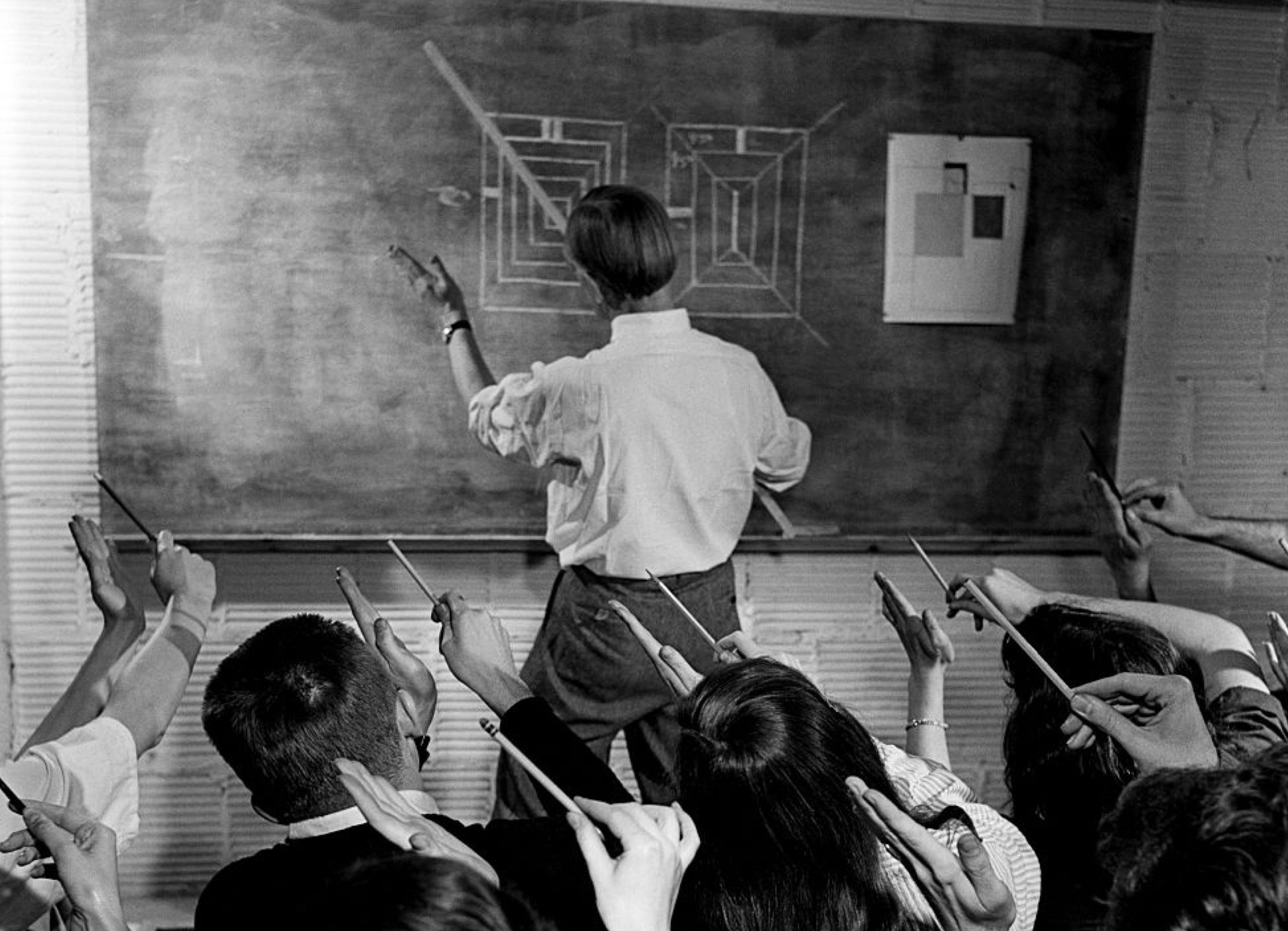

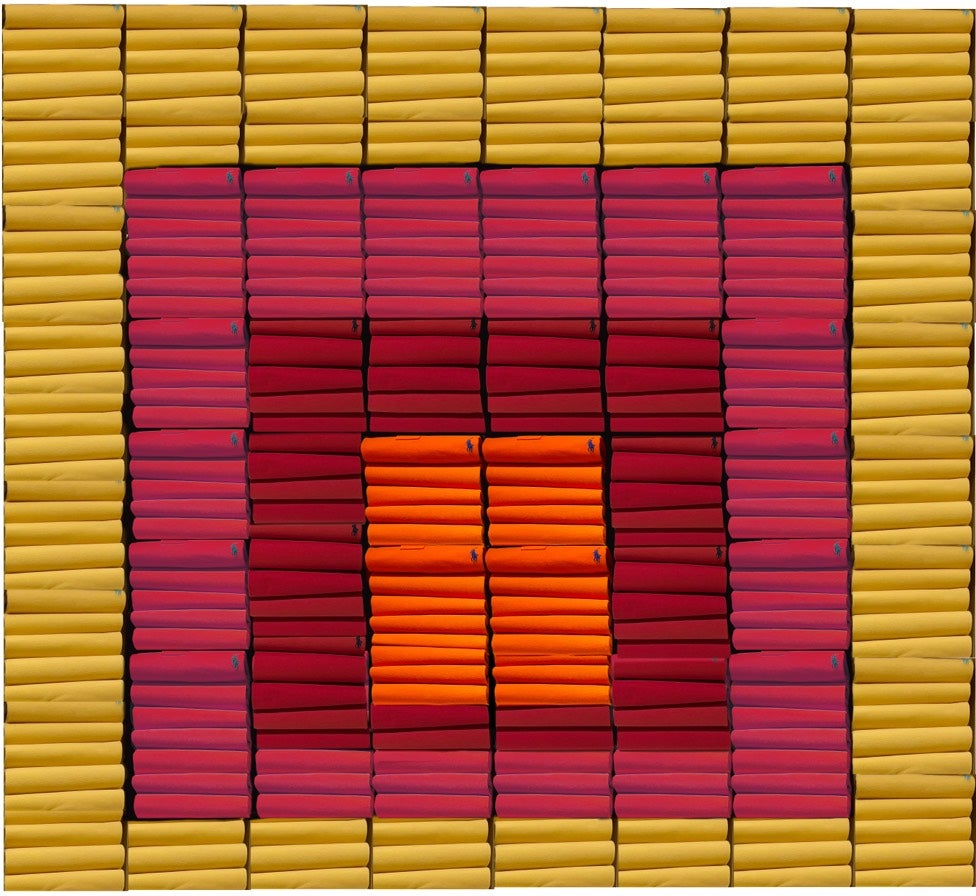

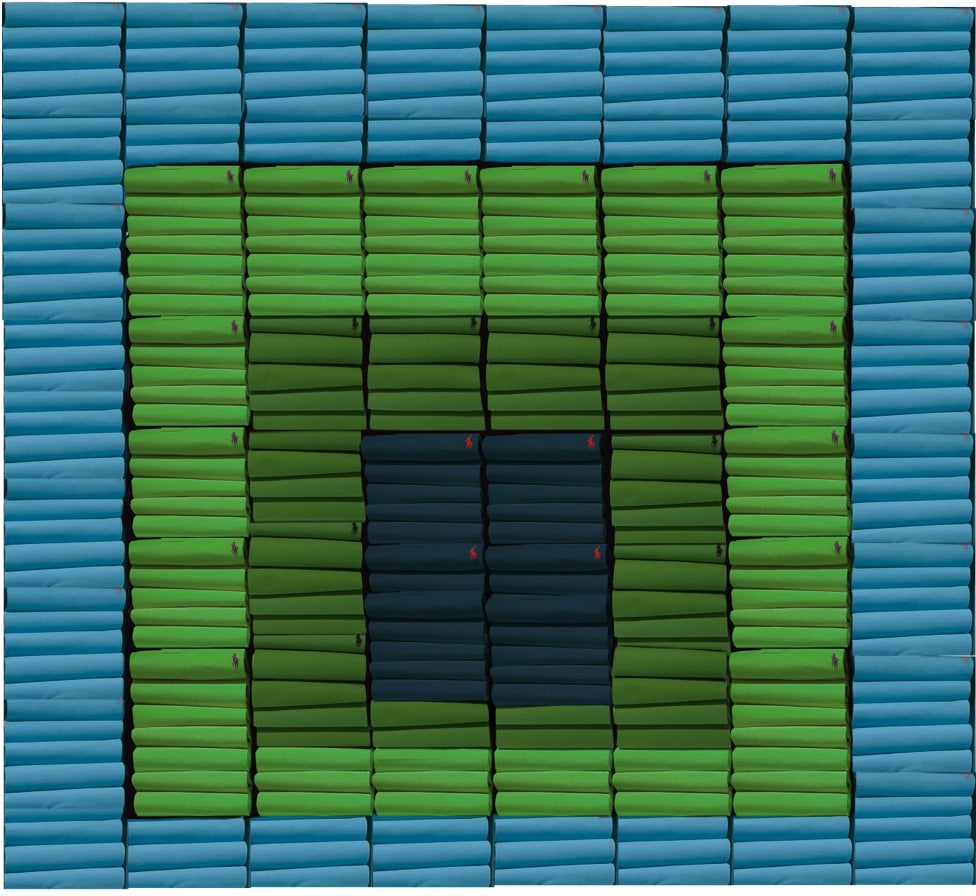

Above: Albers’ lessons in color inspired us to use a dynamic assortment of this season’s Polo shirts in an arrangement that pays tribute to two of his paintings: Soft Spoken, 1969 (left) and La Tehuana, 1951. Such unexpected combinations are a hallmark of refined style. Below: Before joining the faculty at Yale, Albers taught at Black Mountain College, where he was photographed with students. Bottom: A mural by Albers in the Corning Glass Building on Fifth Avenue in New York City.

But in an era when hard-drinking Greenwich Village artists were putting American art on the map, Albers’ sober dedication to teaching didn’t do him any favors. “Albers was respected as a teacher, which was something of a condemnation,” Donald Judd wrote in a late-breaking mea culpa. The modest size of each Homage, 2 or 3 or 4 square feet, which he could easily carry to class, was also out of step with the times. “Big paintings were the fashion,” Judd wrote. “So for a second reason, Albers’ work was disregarded.”

I want to apologize to Albers as well: When I arrived at Yale, two years after his death, the former department head still cast a long shadow, and I wanted nothing to do with all that rigor. My daughter is about the age now that I was then. When I showed her a catalog of his 1988 retrospective at the Guggenheim, she too, another generation of art student who thinks she knows everything, dismissed them at a glance.

Perhaps the lessons take time to absorb. Certainly for Albers, experimentation and discovery were enough. He lived modestly and worked with a tradesman’s diligence, painting from the center outward, the way he’d learned from his father, who painted doors like that. And color rewarded his diligence with its secrets. His treatise on the topic, Interaction of Color, is a compendium of effects and how to conjure them. In one page of circles of equal size tightly connected in vertical and horizontal rows, he varies the colors of the background and the circles to an almost musical effect. His accompanying advice to the student seems to hide a personal confession of faith: “We recommend such organization of ‘restricted means,’ because a limitation in one direction often opens up more freedom in other directions.”

By 1970, his studiously small Homage series had brought him fame and financial reward, and he and Anni moved from their small home in New Haven, Connecticut, to an almost identically modest one in a greener New England suburb nearby. Albers had a heart condition by then, and they chose a home close to a cemetery, so whoever survived could drive by and wave. Those were their practical considerations. But it also seems relevant to note that out of all the leafy towns in the Land of Steady Habits, Albers chose to end his days in the only one named for a pure color: Orange, Connecticut.

The Polo Gazette

Issue N˚ 10