The Birth of Bond

Ian Fleming was, in many ways, the prototype for his creation. He cared about the finer things, dressed impeccably, and was a master of espionage—and the martini. A new biography brings his story to life with the pace of a thrillerIan Fleming made a disastrous marriage, out of which was born James Bond. Fleming’s wife was Ann, granddaughter of an earl and sister to the Duchess of Marlborough. Ann married a baron before upgrading to a viscount to become Lady Rothermere, wife of the owner of the Daily Mail. A conscious exemplar of class and taste, Ann was accustomed to being—and being around—the fabulously rich and was casually brutal to Fleming after finally taking his name as her third husband. She punished him above all with parties, which he loathed, and her true love seems to have been the one thing Fleming would never have quite enough of: cash. At their wedding, Noël Coward was best man and lunch was the turtle Fleming caught himself that morning, off the rocks of Jamaica, where he had a property at the water’s edge named Goldeneye and would spend more and more time. Fleming’s own assessment of the union’s prospects was, “China will fly, and there will be rage and tears.” Though it was not porcelain but another man who truly killed it all in the end: James Bond, the character Fleming created and who, many historians have argued, single-handedly saved the British Empire’s sense of self during its decline.

Fleming never thought much of Bond. Nor did Ann who, upon the publication of Casino Royale, the first book in the Bond series, refused her husband’s offer to dedicate it to her. Bond was built to keep the Fleming’s lives financially afloat (“My profits from Casino will just about keep Ann in asparagus for Coronation weekend,” Fleming wrote to a friend). Casino Royale was published on April 13, 1953, and Fleming chose the title hoping it might be mistaken for a story about England’s new queen, Elizabeth, and that sales would bump as a result. They did not. Though, as we all now know, they would. Bond would eventually exemplify modern Hollywood’s favorite word: “franchise.” It is a word which rings more of money than of meaning.

From top: Fleming, in 1964, on the beach of his beloved Jamaica, where he spent much of his time; on a walk in London with his wife, Ann, who was “casually brutal to Fleming after taking him as her third husband”; a rare first edition of Thunderball, the ninth book in the Bond series, which was published by Jonathan Cape in 1961, and the colorful Signet paperback editions, which began to appear around the same time

From top: Fleming, in 1964, on the beach of his beloved Jamaica, where he spent much of his time; on a walk in London with his wife, Ann, who was “casually brutal to Fleming after taking him as her third husband"; a rare first edition of “Thunderball,” the ninth book in the Bond series, which was published by Jonathan Cape in 1961, and the colorful Signet paperback editions, which began to appear around the same time

And yet the story of James Bond is only a small part of the truly riveting story of Ian Fleming. Nicholas Shakespeare’s new biography of the novelist, The Complete Man, only finds its way to the novels almost 400 pages in. It turns out that the Bond period of Fleming’s life, coinciding with his unhappy marriage, is the least interesting thing about Fleming who, in photographs holding a lit cigarette in a long holder, is the picture of a certain kind of Englishman—decadent, idle, boring. Yet Fleming was none of those things. So, it is poignant to discover that in the years he was writing his iconic spy thrillers and, later, experiencing their ecstatic global following, the thing Fleming wanted most was to return to another time in his life—the war years, when he had almost single-handedly designed, launched, and led a private, elite commando unit.

The part of The Complete Man that reads like a thriller has nothing to do with martinis or girlfriends. Fleming, as it turns out, was a far finer, more serious spy than Bond. He served a unique role in the war as the British officer chosen to work with “Wild” Bill Donovan, the man most often cited as the founder of America’s Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, the organization that evolved into the CIA. Fleming’s mission was to create a new American intelligence corps modeled closely on Britain’s SOE. His greatest work of art, and he knew it, was not Octopussy but rather 30AU—30 Assault Unit—a team which grew to almost 500 men by 1945. Known as “Fleming’s private navy,” 30AU was there on D-Day, and in Cherbourg; they oversaw Operation Woolforce II, the liberation of Paris. They were the team that hunted German scientists as the race to build the bomb took shape and the ones who accepted the formal surrender of the German navy in Kiel. When 30AU raided Germany’s Schloss Tambach and retrieved a cache of priceless German Naval records and documents, it was a generational intelligence coup. Their legend was set. The number “30” was a nod to Fleming’s secretary’s room number at the Admiralty, the Royal Naval offices. One of the unit’s last surviving members, interviewed by Shakespeare, tells him that the 30AU records will remain sealed until 2050. And yet if you do read the Bond books, you see glimpses of the cowboy style that defined those kinds of covert teams, then and now, teams like the Navy’s SEAL Team Six or the CIA’s Special Activities Division. 30AU, like James Bond, only colored outside the lines.

“Each book is an education in something,” Shakespeare writes of the Bond series. “Gold, diamonds, jet engines, canasta, sharks, bridge, guano, karate, golf. This knowingness is central to his allure.” And it was acquiring such new knowledge that saved Fleming for a long time, until it didn’t, until he finally tired of Bond. Bond gave his creator license to travel and the space to breathe inside an otherwise constrained emotional space. And of course, Bond tapped Fleming’s taste for finer things. “A gourmet for brands and esoteric details, Bond flatters and impresses the reader with abstruse nose-tapping knowledge, not merely about the Latin name for the scorpion fish and that poisonous fish’s relation to rascasse, the foundation of bouillabaisse, but about sex, foreign countries, clothing, drink.” A friend describes Fleming ordering a drink with such demanding detail, “as if it was a delicate brain operation.” Because detail mattered urgently to Fleming. Detail: another way to say control. Everything about Fleming was a signature, like the Morland Specials he smoked, handmade Turkish cigarettes with three gold bands “to represent the braid on his lieutenant commander’s sleeve.” Fleming wanted what he wanted when he wanted it, behavior which might be called spoiled.

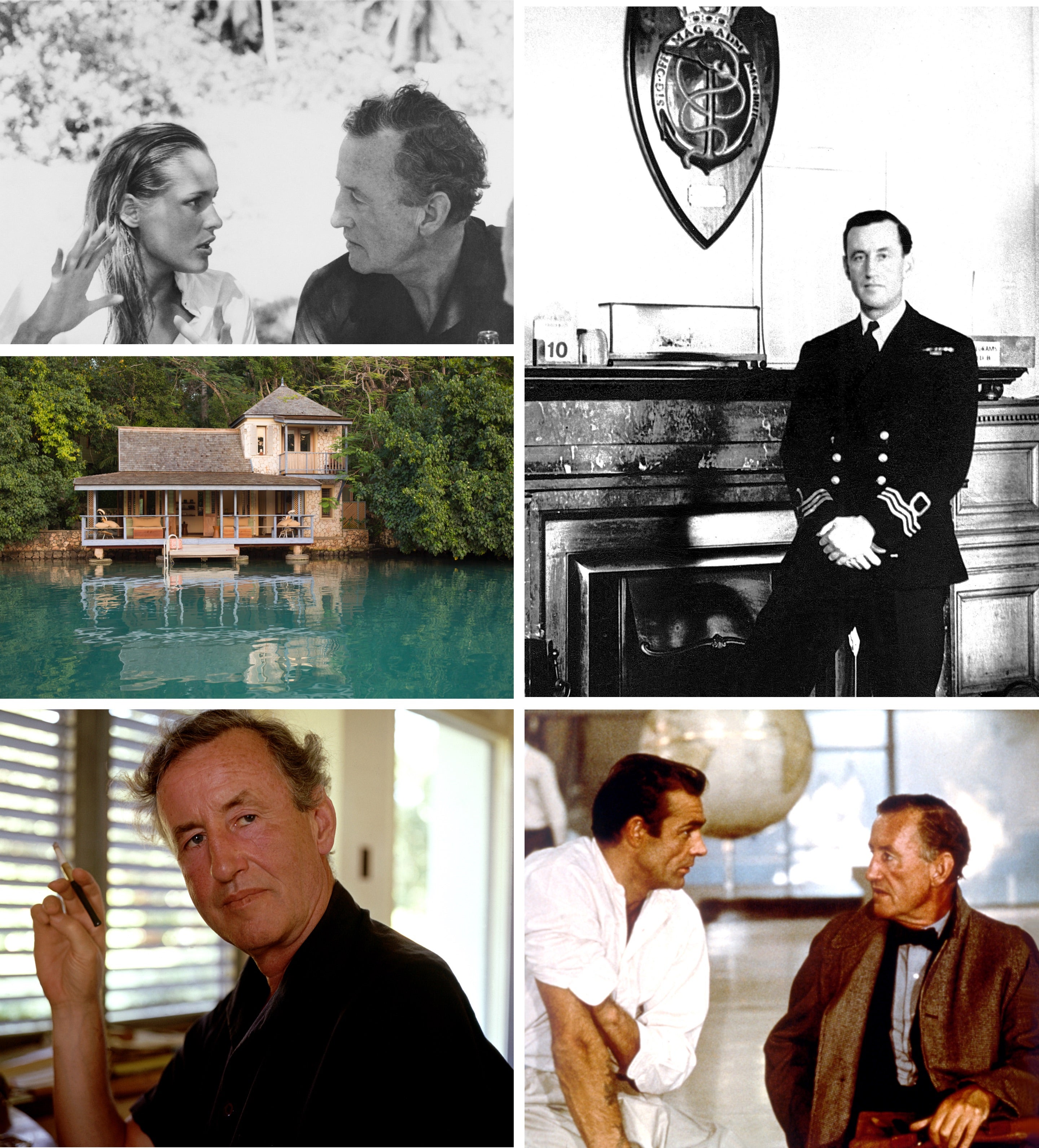

Clockwise, from top: On the set of Dr. No with Ursula Andress; Fleming during the war when he ran 30AU, 30 Assault Unit; on the set with Sean Connery; at his writing desk at Goldeneye; and a view of the villa from the water

Clockwise, from top: On the set of “Dr. No” with Ursula Andress; Fleming during the war when he ran 30AU, Number 30 Assault Unit; on the set with Sean Connery; at his writing desk at Goldeneye; and a view of the villa from the water

“What I endeavor to aim at is a certain disciplined exoticism,” Fleming said of the novels. And that, in the end, may be the best description of their author, too. Fleming was proud of his service in the Royal Navy, which went largely unrecognized. He hated fancy people and fancy parties, once describing participation in a celebrity golf tournament as “the most dreadful experience since the Dieppe Raid.” He would skip the splashy opening of a Bond film to go diving with Jacques Cousteau. It was in the water, especially the sea off Goldeneye, that Fleming seemed happiest, engaged in that “disciplined exoticism,” seeking out truly new worlds.

When Jack Kennedy, concerned about Fidel Castro’s Cuba as he entered the race for the American presidency, asked Fleming “What would Bond do?” Fleming had an answer that included inspiring Cuban men to shave their beards via elaborate psychological ops; history indicates the CIA likely listened. This was the one way Bond mattered for Fleming—he provided a link to the real world of intelligence operations, his North Star. The novels were never meant to be literature; Bond was pure experience. Like Fleming, Bond was licentious because he was bored by love’s “conventional parabola—sentiment, touch of the hand, the kiss, the passionate kiss, the feel of the body, the climax in the bed, then more bed, then less bed, then the boredom, the tears and the final bitterness.” Bond’s chilliness (or silliness, depending on your view) towards women aligns perfectly with Fleming’s one abiding belief: that the greatest love in life is not a person; it is a sense of purpose.

The Polo Gazette

Issue N˚ 10