A Very Shirt Story

Would we be wearing nautical striped shirts if the Lost Generation’s most stylish (and forgotten) member didn’t show Picasso a thing or two about vintage cool? A theoryThe French call it the marinière, the word for sailor, and for good reason. New recruits in the French Navy began wearing them in the 1850s; the long-sleeve shirt, with its horizontal blue stripes and band of white at the shoulders, was designed to help distinguish sailors from the waves if they fell overboard. Along with the beret, a Citroën DS, and, perhaps, a Gitanes between the fingers, there is almost nothing more symbolic of French style at its most—je ne sais pas—existential level.

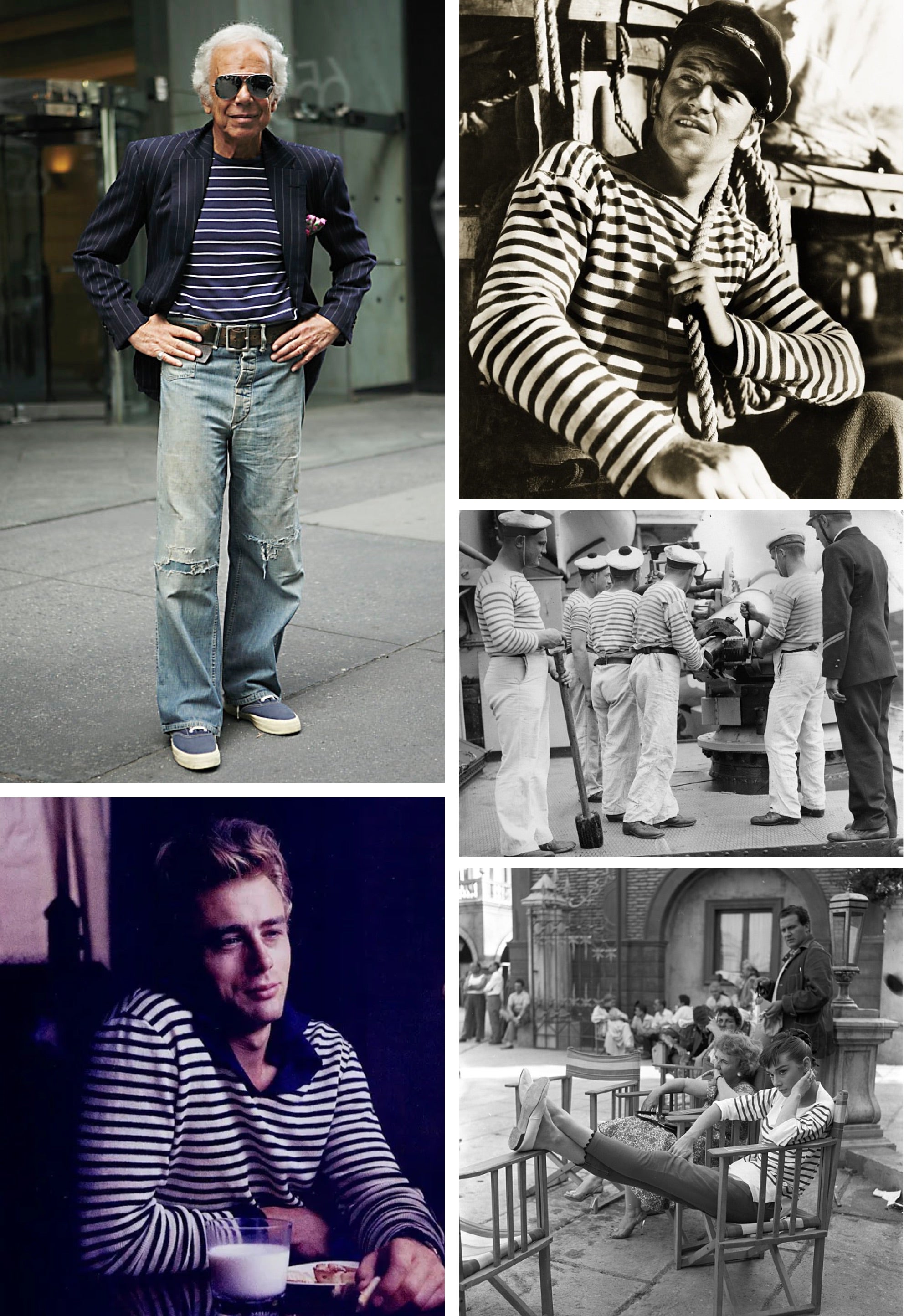

Pinterest abounds with formative marinière moments: Jean Seberg in Breathless, John Wayne in Adventure’s End, James Dean being James Dean, and Picasso in his various rambling Riviera art studio lairs. When not in his natural state of shirtlessness, the poster boy of nautical stripes appears to have had little else to ensconce his girth. A bull of a man, he was as physically demanding of his clothes as he was of iron, scrap wood, and globs of paint. Pattern on him no more obeyed the rules than it did on one of his canvases; stripes meant to be horizontal bunch, waggle, and bend across the barrel of his chest as if nothing that followed a strict order could do so for long in his proximity. Still, Picasso imbued the marinière with the Promethean glamour of a 20th-century modern genius, and the shirt has been working that chicly avant-garde angle ever since.

Ralph has been riffing on the marinière for years, styling it in a way that shows how something of simple perfection can be dressed up or down; John Wayne in Adventure’s End; a crew of French cadets, 1935; Audrey Hepburn takes a break on a movie set, 1955; James Dean wears Breton stripes; and, below, Picasso, in his studio near Cannes, 1960

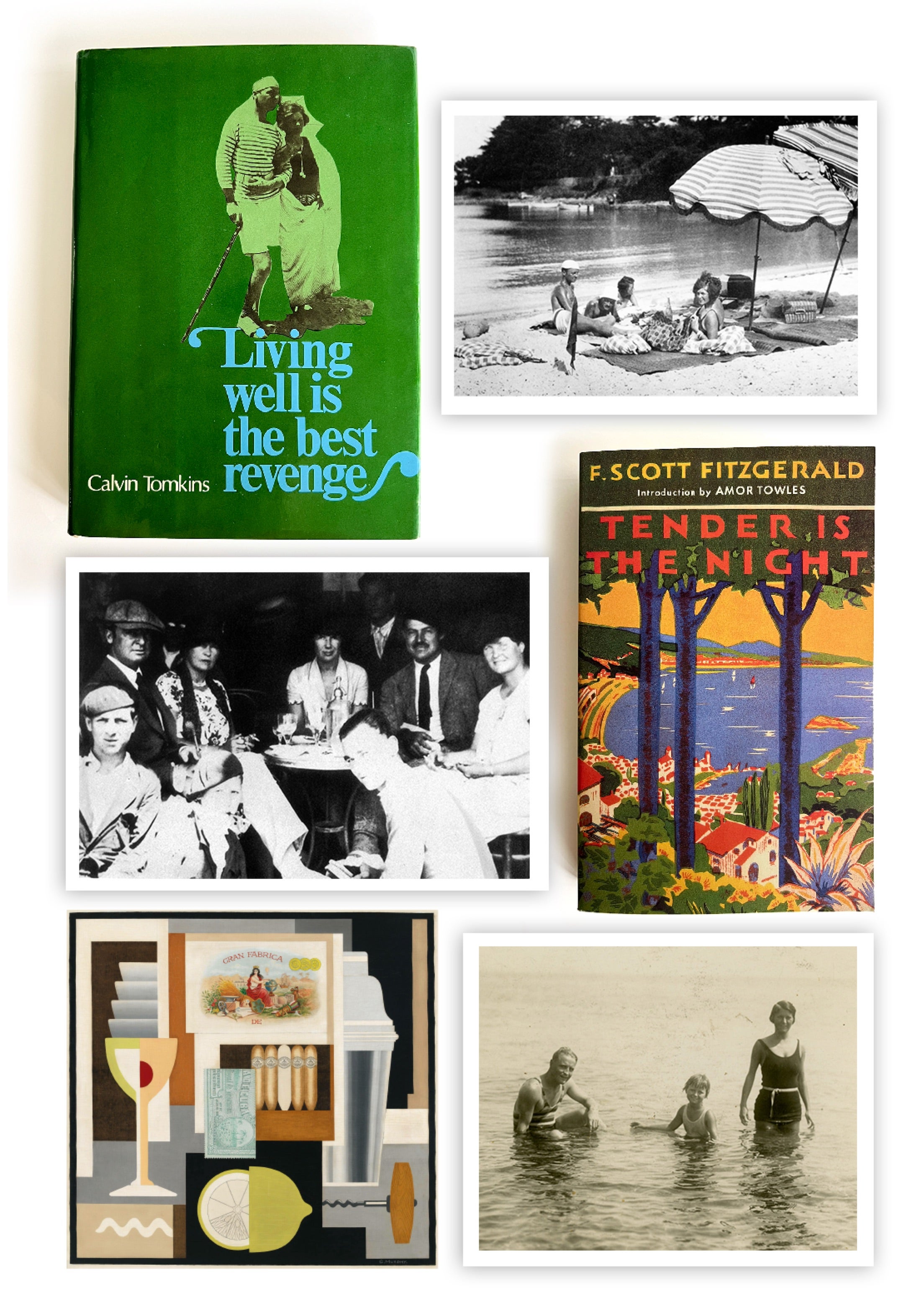

But was Picasso really the first magpie of vintage style to appreciate the marinière’s combination of usefulness, graphic charm, and durable versatility? It is, of course, hard to know for sure, but that shouldn’t keep us from making an assumption by rereading Calvin Tomkins’ Living Well Is the Best Revenge, his 1962 classic of Lost Generation commentary, and a wonderfully escapist read that is wistfully short: just 148 pages. In it, Tomkins tells the story of Sara and Gerald Murphy, a moneyed American couple whose name you may not know but whose influence on our modern conception of the charmed expat life abroad between the wars is nothing short of fundamental.

Murphy’s father founded Mark Cross, the Fifth Avenue purveyor of leather goods and exotic collectibles that was, in its heyday, the equivalent of an American Dunhill. After graduating from Yale, where he was a member of Skull and Bones and struck up a lifelong friendship with Cole Porter, he rejected his father’s offer to work in the family business and moved to France with his wife and young children, where he spent the next 10 years studying to become a painter. (He was a good one; works by him concerned with subject matter Pop Art wouldn’t take up for another four decades are in the collections of both MoMA and The Whitney.) A pair of bon vivants with a talent for entertaining and impressing others with their enchanting interpretation of life, they quickly fell in with the artistic firmament—Picasso, Stravinsky, Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, Legér, the Fitzgeralds—then flocking to Paris as the beacon of artistic daring and achievement.

The book jacket of Tomkins’ indelible story of the little remembered but enormously influential Murphy couple; the Murphys on the beach in Antibes in the 1920s, when it had yet to be discovered; Fitzgerald based the main characters of Tender Is the Night on the Murphys; the novelist—photographed here with his wife Zelda and daughter Scottie—didn’t like to swim yet when he visited the Murphys he wore stripes; Cocktail, which Murphy painted in 1927, is in the collection of the Whitney Museum; the Hemingways and Murphys with friends in Pamplona, Spain, for the bullfights, 1926

The Murphys, who then stumbled upon Antibes at Porter’s urging before it became a fashionable destination and one summer rented out the entire premises of the then unknown Hotel du Cap, so captured Fitzgerald’s imagination that he closely based the characters of Nicole and Dick Diver on them in Tender Is the Night. Of Diver, Fitzgerald, in a famous line, writes: “He looked at her and for a moment she lived in the bright blue worlds of his eyes.” He is further described as a man who “represented externally the exact furthermost evolution of a class,” the type who holds his jacket in his hand like “a toreador’s cape.”

This was, if you read Tomkins’ book, and you should, pure Murphy, who inherited his father’s eye for desirable things and swept people up in his stylish wake. “Those closest to the Murphys found it almost impossible to describe the special quality of their life, or the charm it had for their friends,” Tomkins writes, noting that only Murphy could have dressed like he did. His clothes, he writes, would have been “a trifle too elegant if anyone else had worn them.”

Perhaps the marinière was the one thing he owned that was different. With its humble, workwear beginnings, and ease of being thrown with just about anything, the marinière was something the Murphys’ friends could wear themselves. “Gerald’s ‘functional’ sailor’s jersey ... became standard gear on the summer Riviera,” Tomkins points out. This included, Picasso, as noted, and also Hemingway and Fitzgerald, who didn’t even like to swim. Thus, from a small but loyal American following, a very French shirt would go on to conquer the world.

The Polo Gazette

Issue N˚ 10