Write of Way

Artist Rajiv Surendra’s passion for calligraphy celebrates the joy and beauty of a forgotten craftThere’s no mistaking Rajiv Surendra. He traipses through Manhattan atop his vintage German bicycle, circa 1940, with a basket on the back that’s often brimming with an arsenal of pens, papers, and envelopes.

When he was just 8 years old, Surendra, who is now 32 and an actor, artist, and published author, started receiving written letters from Lakshi, a cousin in Sri Lanka whom he had never met in person. Growing up in a suburb of Toronto, he remembers the thrill of receiving a parcel sent via international post, with its distinctive blue-and-red striped edge. “As soon as you open the mailbox, you would see right away that there was a letter from Sri Lanka, and her letters were spectacular,” he recalls. “Her penmanship looked like it was printed on a typewriter. She would score the lines on the page, and she would do little, beautiful colored pencil drawings on them; sometimes a deer or little flowers.” When they finally met in person over a decade later, the two felt an instant connection.

Since then, the thrill of writing and receiving correspondence has grown infinitely for Surendra, who, in addition to his work as an actor, has a boundless love for penmanship and calligraphy, which he explores under his “Letters in Ink” moniker (@lettersinink). During our first meeting, which occurred by chance at a West Village coffee shop, he had spent nearly three hours writing a letter to a family in Berlin, where he once served as their au pair. The letter spanned 12 pages and included a watercolor of the townhouse across the street from the shop, complete with flower boxes and beams of sunlight.

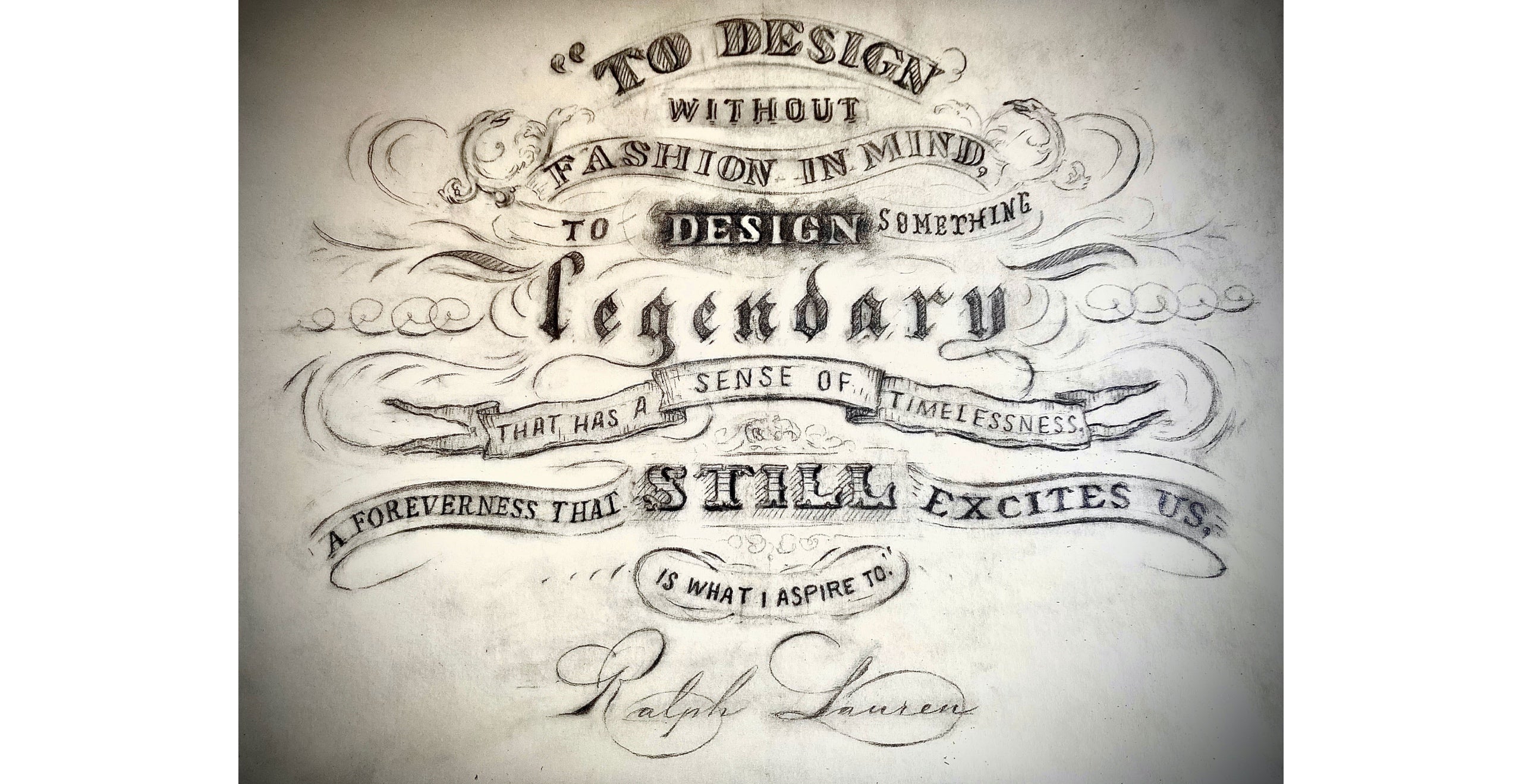

Thumbing through one of Surendra’s letters feels akin to handling a Victorian-era document, which is precisely what set him down this path of obsession at the age of 12. “I volunteered at a living history museum, and someone there showed me some very old letters from the 1800s,” he says. “Their handwriting was like artwork, and that’s what inspired me to start to learn how to really do calligraphy, because I wanted my handwriting to look like the writing in those old letters. That was enough to just make me push and try.”

He began by mastering the capital W, in George Washington’s signature on the Declaration of Independence, a seemingly menial task until one takes into account its varied weights and delicate curves. These days, he can produce an exact replica of the signature in mere seconds on the back of a coaster.

His taste in materials can change with seasons or his mood or the contents of the message he is sending. At the moment, he prefers a thin, featherweight paper made by a Japanese manufacturer. “It’s kind of hard to read because it’s almost transparent, and I love that the person receiving the letter has to find a place to put it down and read it,” he says.

What does not change is his preferred letter opener, a rusty black pen knife found at a garage sale in Rhode Island for 50 cents, which he has sharpened every so often by a cutler on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. It’s a small but essential piece of Surendra’s letter-opening experience, which is a precise ritual. “To this day, when I open my mailbox and there’s a handwritten letter, my heart leaps,” he says. “So I take it up to my apartment, and I put it on the pillow on my bed. I wait until I’m ready to get into bed, and then I get the letter opener, climb into bed, turn on my night-light, open the letter, and read it in bed, right before I go to sleep, like as a reward for waiting for it.”

It’s an exercise in self-control, meant to honor the time the writer has put into their correspondence. “I say this over and over and over again, but there is no greater gift that someone could send me than a handwritten letter,” he tells me. “That is the thing that gets to me the deepest. It’s very, very powerful that someone’s sat at a table with this paper and a pen, and all they thought of was you, and there is proof.”

When it comes to writing a letter to others, it’s a less rigid affair. Surendra enjoys the stream of consciousness and the unsolicited prompts in the world that may spark him to write to a friend. His mistakes are often left purposefully visible, so as to display his adjustment in word choice or his unabashed excitement, and he never places a timeline on when a letter must be completed and mailed. “When you’re writing in fluid strokes of calligraphy, you can’t stop,” Surendra explains. “You can’t just do it for three minutes or five minutes, or 10, or 30. Usually, a letter takes me about an hour, and you are alone while you’re doing this, but in a way you’re also with the person you’re writing to.”

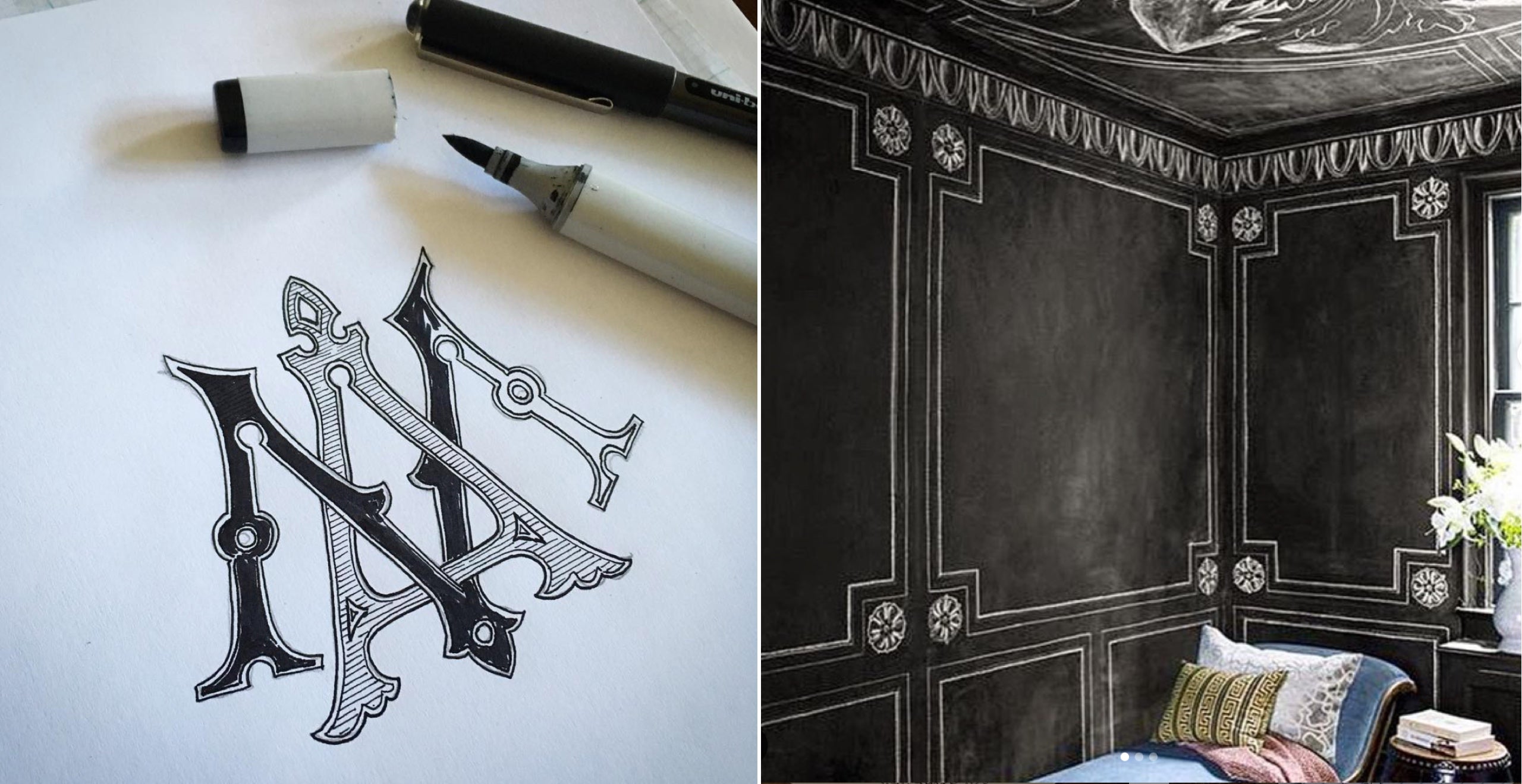

When the situation calls for it, Surendra isn’t afraid of chalk either. Nearly a decade ago, while enjoying coffee with a friend at an outdoor café in Toronto, he noticed an A-frame chalkboard sign with, what he says, was “hideous” text. “Right then and there, I went up to the owner and asked, ‘Can I redo that for you?’” he recalls. “It was a beautiful summer afternoon. I knelt down on the sidewalk and spent about an hour on it.” The results were so impressive it caused a small tidal wave of elevated chalkboard design across the Toronto dining scene.

At the annual Kips Bay Decorators Show House a few years ago, Surendra collaborated with celebrated interior designer Garrow Kedigian on a drawing room covered in intricate chalk designs, ceiling included. The project took seven full days to complete and came to be known informally by showroom visitors as “The Chalk Room” before meeting its fate with an eraser. “What I really loved about this medium is the fact that it can be erased,” he says. “We all went to school where chalk was used on a blackboard, and we understand its nature. It’s very fleeting, and it’s really come to represent, to me, what life is all about. You may think you have a 10-year plan, but life has a way of telling you, ‘No, I’m in charge.’”

Whether chalk or ink, it is in this process of creation, the blossoming of one’s dedicated skill set into a completed work, that Surendra has found himself most fulfilled from an early age. “That has always been a source of pride for me,” he says. “If you can make something, and you can make it well and share it with someone, you will feel good about yourself, and that’s never left me.”

- All images courtesy of Rajiv Surendra